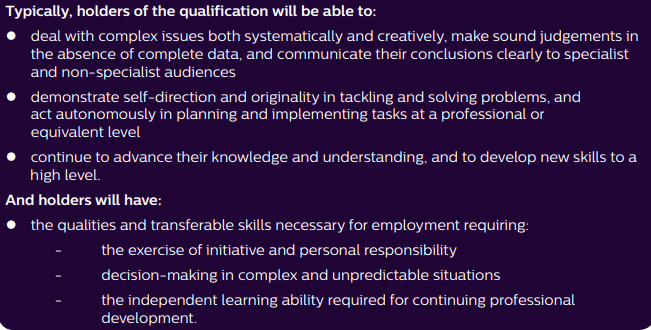

We’ve all had the lecture. You can only hold so many items in your working memory because there are only so many slots. It’s in the Core Content Framework (CCF) for trainee teachers. It’s in the Early Careers Framework for recently qualified teachers. And it’s in all the NPQs. If I undertake sequence of colour, number, or items of information tests on you then, after between four and seven items, depending on context, you cannot remember the sequence accurately. Here is what it says in the CCF:

And so we break down instructions into small ‘chunks’. We think about capacity all the time and use it for instructional coaching. Granularity is key. But that idea of working memory having a limit, having only so many slots, is not the only idea in psychology. There is another theory which has just as much validity as the fixed idea. An idea that suggested we could be using many more items than 4-7 in teaching and it would still work. Welcome to the world of low resolution memories…

One competing idea is that the limit on capacity is based on resource rather than a fixed number of slots. It’s nothing new – it’s been around as long as the ‘slots’ idea and instead of slots, it says that working memory is a fluid pool of resources. In other words, you can remember a few things with precision, but that when you overload working memory the result isn’t a total failure to remember additional items, but a degradation in the quality of the memory of all eight items. It’s like pouring your working memory into 8 jars instead of 7. It’s spread around more thinly. The more items, the more pixelated (to use a modern term) the memory. If you want sharp resolution, then keep the number lower, if the outline is important and you’ll be adding resolution over time then the detail isn’t so important at the start. For example, an important part of kinesiology is knowing all 206 bones in the human body. But you still start with the skeleton of all 206. You will probably then divide the skeleton up into groups of more than 4-7 bones. You add detail as you go down so that magnitudinally, the memory can zoom out and in as it is needed. In many ways, it makes good sense to start with a very poor pixelated skeleton memory and then build detail up, rather than start with small detail of 4-7 items. Having the ‘whole’ in your memory, no matter how grainy, can work well when adding detail later on and being able to construct the fine detail into the whole picture.

Where else might this begin to make sense in teaching? Well, certainly in English. One of the first things you do before teaching an extended text is to teach students the plot. If you are teaching pupils The Merchant of Venice then you teach students about the pairs of characters, the love interests, the racism, the basic plot around the borrowing of 300 ducats by Bassanio, through his friend Antonio, to pretend to be rich in order to woo Portia (Bassanio really doesn’t come out well in this play), the cross dressing and even the idea that Portia is played by a man who cross dresses back into a man to play the young lawyer. It’s a fiendish plot and one of Shakespeare’s more simple plays! But we absolutely teach the plot first using name tags, bags of gold and solid drama pedagogy. And all those items are not only more than four to seven items but the pupils won’t remember much of it…in great detail. However, as we go through the play and its key scenes, so we will add detail and so that grand plot will come together just like the skeleton with the 206 bones. Once that has happened, then our pupil can zoom in and out of the play examining themes, character evolution and key quotations at ease as they consider the play through the lens of a question. They can recall the large plot of more than 4-7 items and also add detail to each subsection of the plot. This idea is reinforced by one the earlier ideas about resolution rather than slots from this paper by Frick (1988) which found the parsing of knowledge (separating knowledge into items) did not happen as the knowledge entered working memory, but at the point of recall, something he calls the ‘process of recovery’.

Working memory is a finite resource. But rather than see it as restricted to 4-7 parsed slots, begin to see that depending on context and the pupil’s individual strength of working memory, resolution is that which is affected rather than number of items. And then, even further, start to think about delivering something that won’t be recalled immediately in fine detail. Deliver a whole worked example in its entirety first and then go through each section of the worked example in detail.

One issue for us all is why the CCF eschews this contrasting idea of resolution from its literature review. You can still overload working memory, but you are only overloading its ability to create memories with fine resolution. And then Frick would say the parsing happens on the recall, not on the initial learning so there’s further debate there.

There is clearly a place for lower resolution memories in teaching in terms of bigger and more complex sets of data. By adopting the idea of resolution you begin to work with magnitudinal ideas. You can move along the magnitudinal spectrum and allow pupils to zoom in and out of schemata seeing both overarching and complex pictures whilst they are also able to focus and recall fine parsed detail. It’s an important refinement to the idea of working memory and cognitive load and we have to, as teachers, consider how that affects the way we approach our teaching.

Copyright © Dr James Shea and Dr Gareth Bates 2023

Twitter:

Dr James Shea https://twitter.com/englishspecial

Dr Gareth Bates https://twitter.com/smashEDITT