At university, if we want to initiate some kind of intervention in schools as part of a research project we would be expected to review the British Educational Research Association’s (BERA) guidelines. This guideline is full of sensible advice such as:

Researchers should immediately reconsider any actions occurring during the research process that appear to cause emotional or other harm, in order to minimise such harm. The more vulnerable the participants, the greater the responsibilities of the researcher for their protection. (BERA, 2018, p.19)

So the first thing we have to consider is the likelihood of the intervention causing harm to the pupil. And the second thing we need to consider is that a pupil’s ‘vulnerability’ amplifies our need to protect the child from harm.

Now let’s turn to schools. If a member of staff in a school or group of schools wishes to initiate some kind of intervention as part of an evidence informed project to increase outcomes for the pupils or schools what guidelines do they have to follow? Well, the answer is, quite simply, none. Yet, if they did the same project in their school as part of undertaking a PGCE or Master’s then it would have to go through the exact same ethical approval process as described above.

It is important and worthwhile at this stage to set out that I am not talking about low level interventions of the sort that schools and teachers do all of the time. I’m talking about practice which could cause harm. And to vulnerable pupils in particular.

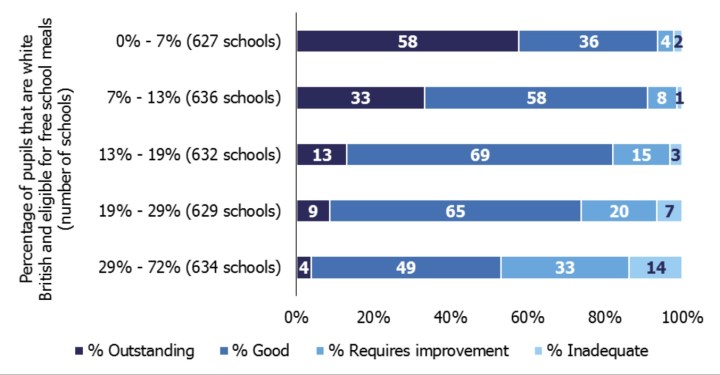

Let’s take off-rolling as an example. Here we see that staff in a school or group of schools have decided to create an intervention. The intervention could possibly benefit the pupils in the school cohort through redistribution of resources. It could even hypothetically benefit those who leave the school through the process of off-rolling. As part of an ethical approval process you would evaluate the likelihood of harm falling to those who are being off-rolled and look at the outcomes for them after they leave mainstream schooling. Well, it turns out the outcomes for those who leave mainstream schooling are poor: 1-6% get their 5 good GCSEs. That’s considerable harm. Then you evaluate who is being off-rolled. Well, it turns out it is SEND pupils amongst others. I think we can safely say that they meet the term ‘more vulnerable’. This intervention would have died at the proposal stage at the table of the ethics committee. Even internal off-rolling such as a grammar school preventing Year 12s from moving to Year 13 if they did not attain specific grades would most certainly fail the ethical test.

But here is the rub. These schools that are off-rolling pupils are ‘compliant’. They meet the requirements that are set out by the accountability framework. The DfE doesn’t approve, OFSTED doesn’t approve, the children’s commissioner for England doesn’t approve, parents struggle to get provision for the SEND children or a second year of A level education for their children and yet despite this, schools are ‘compliant’.

So is that the requirement? That schools have to be ‘compliant’ and that this does not take into account ethics? Should not all major decisions of this type have to go through an internal ethical panel which in itself is reviewed and checked by an external ethical body? If schools are to be more evidence informed does it not also follow they should be ethically sound? Should governors and trustees also be part of this ethical process and receive training?

Before you say this is unworkable, consider how it is done at university. If a student proposes an intervention they have to write a section on ethics setting out how it meets the ethical requirements. It is reviewed by a qualified tutor. There is an ethics board for more contentious interventions. At each stage, if there is any doubt about the intervention, it is passed up further through more senior boards, staffed by more experienced and qualified senior professionals. The bigger the proposal, the more scrutiny for ethics it attracts.

The government could legislate against off-rolling easily and the affected schools would all change their actions and become ‘compliant’ again. Until the next ethically challenging idea thought up to affect outcomes within the accountability framework. Wouldn’t it be better to also have a headteacher’s body draw up a code of ethics similar to that from BERA and for all teachers and schools to use this when considering evidence informed interventions for their pupils?