One model of explanation often applied in determining the learning and behaviour of any child is the state their Autonomous Nervous System (ANS) is in. It is worth knowing a bit about this as the ANS gene expression is changed by poor early attachment experiences, excessive stress and trauma.

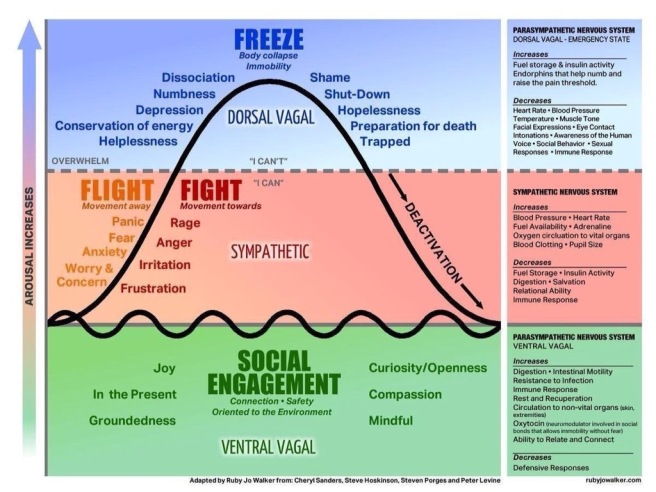

In any situation, a child’s brain is neuroceptively (fast and unconsciously) assessing environmental safety. Many children find school a reasonably safe place and respond accordingly; some will find school and learning unsafe. This blog does apply to all children, but focuses by illustration on children who have experienced adverse childhood experiences. If a child’s life means that their experience of things is fraught with danger signals, then the child’s ANS will be sending danger signals to the rest of the brain and to the body. The child will then excessively look for danger in the EXTERNAL environment and excessively experience danger INTERNALLY – even from the most unfathomable of stimuli; when we experience an internal feeling of danger we tend to look externally for the source. This chart by Ruby Jo Walker highlights it well.

According to Stephen Porges, who has pioneered work on the role of the vagal nerve, the ANS operates on a continuum of response from complete safety to extreme danger. It is helpful to divide this up into three zones of SAFETY, DANGER and LIFETHREAT. When the ANS judges both internal and external environment to be safe then this represents a child’s optimal arousal level. In this state, the child is most ready to learn. This is not about an element of challenge or stress but the assessed absence of danger. It is this state, that most children are in when in school, that is elusive for the child who has experienced significant adverse life experiences.

A child with the above issues exists far more with the ANS in a state of readiness for danger or even life threat – even if no such threat exists in the environment. A danger state is represented by hyperarousal and readiness for fight, flight, rage or panic. A life threat state is represented by hypoarousal, freeze, dissociation and collapse. When someone has an extreme phobic response to a relatively innocent stimulus then this is what is happening.

This understanding sheds some light on the issues surrounding these often very difficult to manage children. We tend to look at our external environmental strategies to see if they will work and often cannot see why they don’t work. However, these strategies simply will not work if the ANS is experiencing the external or internal child environment as dangerous. Where does this leave us then? Our focus needs to be on getting the ANS in the right place rather than on the poor behaviour resulting from the ANS response. Quite simply we also would behave in inappropriate ways if our ANS was misfiring in this way. When working with these children it is helpful for us to acknowledge poor behaviour and response to learning as adaptive rather than maladaptive. That leads us to the question, ‘Why might this behaviour be adaptive?’. Once we have asked ourselves that question it can lead us forward in our search for good solutions.

We can take three routes to modifying the ANS response and in ‘learning the child’, we can try to find the right combination of routes. The first route works primarily on the body and physiological response generated by the ANS. The second route works primarily on the emotional state itself to create a sense of safety. The third route works on the cognitive (executive function) ability to apply a brake to the ANS. This whole brain way of working represents a powerful model for working with these children.

As teachers we need to ‘stand still in order to move on’. This means finding the time to stand back and ask the question ‘ Could this behaviour be signalling something more than is immediately obvious? By being prepared to view behaviour as a signal of adaptation gives us the space to become thoughtful and reflective rather than reactive. It enables us to be better teachers and children to learn better.

Having run a workshop on this a number of times it has become clear educators need solutions. The main solution is re-labelling the behaviour you see as fight or flight. Imagine someone with a propensity for car rage next to you in a car, raging at the traffic – how do you talk to them? What makes them worse? Tell them to stop swearing and they’ll swear directly at you in response! What about if there was a child on a climbing centre rock wall, frozen mid climb? How would you talk to them? What would you say? You certainly wouldn’t threaten them with a sanction if they didn’t move forward! You tell them about how the rope is making them safe. That everyone does this every day and is always safe. To take their time and then when they are ready take tentative steps. Relabel the behaviour and then approach the situation with the right tools. Once you have a relationship, they’ll respond quicker to you when you use the tools. It’s hard having a heightened ANS system, be sympathetic to them. Recognise how hard it must be to live life on the edge of fight or flight constantly and how that gets in the way of learning.

What a well thought through and thought provoking article. Reframing the arousal curve. Brilliant

LikeLiked by 1 person